Will breakthrough security technology solve the next big art heist or make it worse?

The advanced security and technology we have today makes it much more difficult for thieves to commit a similar crime and get away with it; as we’ll learn, criminals have discovered new digital methods to steal from art buyers and sellers instead.

How the biggest art heist in history happened

On March 18, 1990, two thieves entered the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and executed the largest art heist in history. Today—more than three decades later—the 13 pieces of stolen art worth half a billion dollars remain missing.

The thieves posed as police officers and told museum security guards that they were responding to a disturbance in order to gain access. Once inside, they tied up the guards in the museum basement, cut the paintings out of their frames, and 81 minutes later carried the art out of the museum. The FBI has investigated the case for years and received thousands of tips. The museum is still offering a $10 million reward today, which is the largest reward ever offered from a private institution. Although the FBI thinks they have identified the thieves (two Boston-based criminals who died soon after the crime), the paintings have not been recovered and the case is still ongoing.

Thirty-two years later, the museum still has a page on its website dedicated to the theft in the hopes of collecting information about the stolen artwork. Source: https://www.gardnermuseum.org/organization/theft

Weak security measures contribute to the unsolved mystery

There are several theories as to why this crime hasn’t been solved—one of which focuses on the museum’s weak security measures at the time of the heist.

The thieves took the video surveillance tape from the night of the robbery, which was the only version of the recording. Technologies like the IP camera, which was the first camera that could send and receive information across networks, wasn’t launched until 1996 (six years after the robbery). Because of this, investigators never found any footage from the night of the robbery—however, the thieves left behind the recordings from the night before, which showed an unauthorized individual entering the museum using the same door as the robbers. In 2015, the FBI released the low-resolution video to the public, hoping that they could identify either the man who entered the museum or his vehicle.

Although the person was caught on camera, which could have been a promising lead, facial recognition technology didn’t gain popularity and become a high priority until the 2000s after the 9/11 terror attacks in the US, and a forensic database wasn’t available to law enforcement until 2009. IP cameras today have much better long-distance lenses and low-light sensitivity, which also would have made it easier to identify those individuals entering the night before.

Some of the items from the scene of the crime were tested for DNA in 1990, but because DNA technologies and their use for criminal investigations were relatively new at the time, investigators weren’t able to retrieve a usable sample. DNA technology has come so far today that even a single cell could be used to identify someone.

Could a similar heist happen today?

With these advancements in facial recognition, DNA, and video surveillance technologies, it’s hard to imagine thieves getting away with a similar crime. Security experts agree, but say it’s not necessarily these kinds of heists we should be worried about. Physical security is a lot better today because of the advancements we’ve made to keep up with the quickly changing information technology environments.

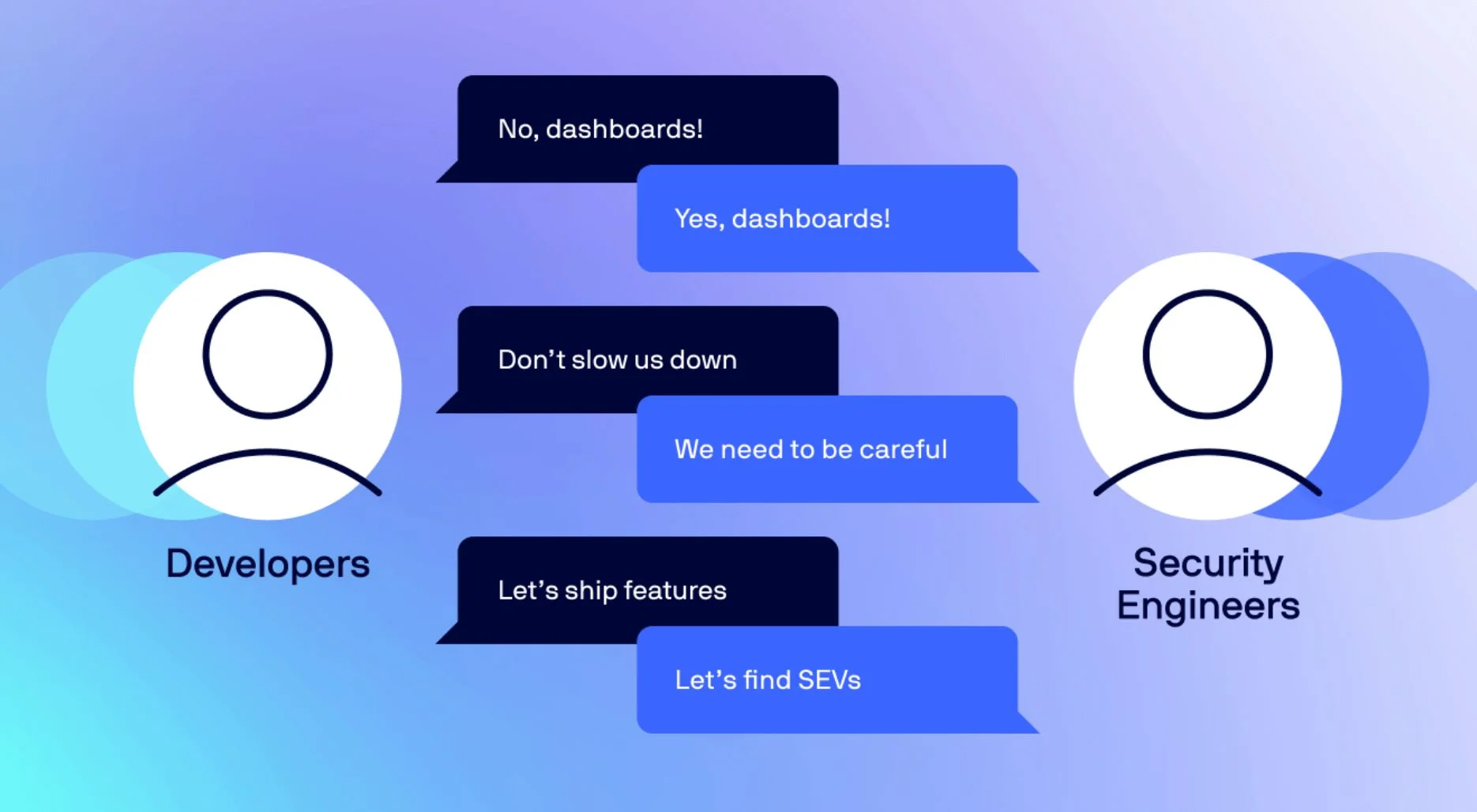

Much of this technology links back to the cloud which is one of the most fluid environments we’ve ever had to secure.

“If a museum operated like the cloud, the museum structure would change shapes and forms every day,” James Condon, Director of Research at Lacework, said. It would be nearly impossible for security teams to keep up with the quickly changing environments without the systems we have today. However, when we apply the technology that we’ve developed with the cloud, and apply it to environments where the structure is staying mostly the same—like a museum—that gives us a huge advantage that we never had before.

Many museums implement controls such as gait analysis to identify visitors’ walking patterns, which can alert security teams if people leave the buildings with more than they entered with. They also use some of the newest radiofrequency ID (RFID) technologies to tag and track artwork’s movement.

As galleries increase online operations, cybercriminal interceptions are a greater concern

“Oftentimes, we think of the worst-case scenarios that we’ve heard of, instead of thinking about the things that theoretically could happen, but we aren’t familiar with,” said Condon.

What could be worse for museums than thieves stealing millions of dollars of art?

A more likely—and potentially more harmful and costly—scenario with all the technology that exists today is hackers getting into systems and stealing art donor or buyer data. Cyber thieves could intercept emails between a business and a paying client and reroute the money to themselves.

So while we’re questioning whether this could happen again, we should really be thinking about whether it could happen differently.

“Sales of high-value art online are growing, and the popularity of online auctions has increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the US Department of the Treasury wrote in a February 2022 report.

Online high-value art sales, such as gallery sales on their websites, reached an all-time high of $12.4 billion in 2020, which doubled its value from 2019. Many art institutions that previously operated entirely at their physical locations tried to quickly adapt to online platforms to reach their buyers and stay in business.

This increase in online art sales, combined with art galleries being new to the online space, is presenting an opportunity for bad actors. The art world is a prime target because they’re transferring very large amounts of money.

As online art cybercrime concern grows, art galleries are trying to alert buyers of the new trends. Sotheby’s, one of the world’s largest brokers of fine art, has a message on its website warning visitors that cybercriminals are increasingly targeting emails and bank account information. They advise visitors that “there is also an increase in the number of scammers fraudulently claiming to be Sotheby’s employees and agents and asking for payment, such as for valuation and ‘security deposit’ for sale proceeds.”

Sotheby’s has a page dedicated to security that warns users about increasing cybercrime. Source: https://www.sothebys.com/en/security-policy

This is a popular method used by cybercriminals in the art industry. They hack into an art dealer or gallery’s email account, monitor email activities between galleries and buyers, and when an invoice is sent, they send a duplicate invoice with different account information and tell the buyer to ignore the previous one. Then, the buyer sends the money to a fraudulent account.

In 2020, hackers posed as a London art dealer selling art to a Dutch museum, successfully convincing the museum to send $3.1 million to a fraudulent bank account. The same happened to many galleries in 2017, including Laura Bartlett Gallery, which closed down soon after the attack and was never able to recover the money. In 2021, Art Basel, the world’s biggest art fair, was hacked by cybercriminals who potentially gained access to personal information of thousands of attendees.

When did data become the target?

In the mid 2010s, the cloud became increasingly popular and was more widely adopted by numerous companies deploying apps in the cloud. This also meant that there was much more sensitive data accessible on the internet. More and more people began discovering databases that were completely open to the public. Hackers recently began using double extortion techniques to download your data and then lock you out of your system and threaten to release your data if you don’t pay a ransom.

With the rise in accessible data and new opportunities to make a lot of money quickly, many bad actors have shifted their target from valuable objects to valuable data.

Valuable art vs. valuable data

The value of art and the value of data are determined by different factors—art depends more on its history, like who it has belonged to, what its historical significance is, and who the artist was.

To identify valuable data, hackers need to determine what’s most important to their targets.

For example, nation-state attackers might look at the priorities of the countries that they’re targeting.

“If a country prioritizes strategic capabilities, the most valuable data to that country would likely be their government’s ‘secret sauce’ or confidential strategic technology,” Condon said.

When a country prioritizes economic competition, the most valuable information is data that will give someone an economic advantage. For example, if a company is selling something, and a third party hacked into a system to find out who the highest bidders were, they have valuable knowledge that they could use to their advantage.

In the private sector, many companies place value on data that would be embarrassing or damaging to their business if it were released. In 2016, hackers stole personal information, including contact information and driver’s license numbers, from more than 57 million Uber drivers and customers. Uber then paid off the hackers to delete the data, but did not disclose the breach to users or the government until the next year. As a result, Uber was faced with lawsuits, damage to their brand, and decreased customer trust, ultimately hurting their business.

Financial data is also often a target because attackers want to use that information for fraudulent purposes such as trying to collect unemployment payments.

The greatest art heist would look much different today

While it would be significantly more difficult for the Gardner Museum thieves to get away with the crime today, art buyers and sellers are still at risk, just like everyone else conducting transactions online. The high value of these purchases makes art transactions prime targets for bad actors, so while technology is a good thing when it comes to protecting art physically in museums, technology can also be used against museums and galleries when cybercriminals use their skills to intercept purchases.

The same security best practices apply to everyone selling and purchasing items online, and protecting your credentials is the easiest and best way to prevent hackers from stealing your information. Enabling multi-factor authentication to prevent criminals from hacking your accounts is a great place to start.

Before you worry about whether infamous crimes that take over the news could happen to you, try to consider the worst-case scenario that hasn’t happened yet. That’s how hackers are thinking, and if you apply that mindset, you can stay one step ahead of them.

Categories

Suggested for you